According to John Bowlby, attachment is the connection a baby forms with its parent to ensure their basic needs of safety, comfort, care and pleasure are met. He described this attachment as “lasting psychological connectedness between human beings”. Bowlby believed that the style of the relationship between the parent (mainly the mother) and the child in this critical period of the baby’s development becomes a blue print for later relationships.

The main idea of attachment theory is that the caregivers provides the baby with a safe and secure base from which to explore the world. The baby knows that it is safe to venture out and explore the world, and that the caregiver will always be there to come back to for comfort in times of stress and discomfort.

Attachment forms in stages from birth throughout early life. From birth to three month, infants do not show attachment to a specific caregiver but show generally positive responses to all caregivers.

From around six weeks to seven month, infants start showing preference for primary and secondary caregivers. They accept care from others but start distinguishing between familiar and non-familiar faces. They develop trust and respond better to their main caregiver.

Around 7 month, babies show strong attachment to their main caregiver and start displaying anxiety around strangers. Between 9 – 11 months, infants start developing emotional relationship with other caregivers (father, older siblings or grandparents). The type of attachment they form depends on the consistency of the main caregiver’s responses, and the quality of their care.

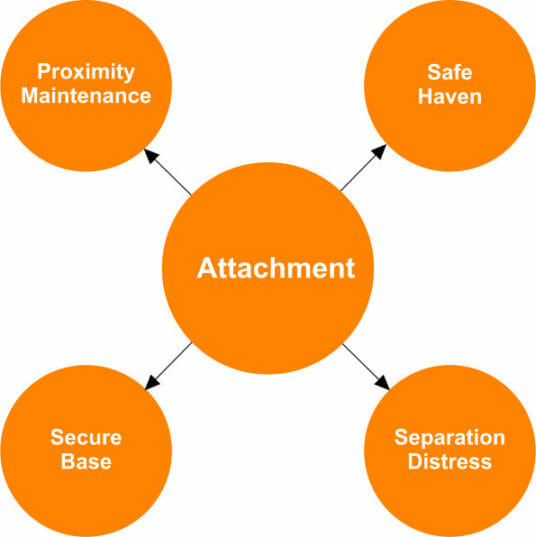

To evaluate the health of a baby’s attachment, we look at 4 components: safe heaven, secure base, proximity maintenance and separation distress.

Attachment Theory Part 1: Safe Haven

According to Attachment Theory, the caregiver in a baby’s ideal life is responsive to the baby’s needs and is a source of comfort and safety. If the baby cries because it feels threatened, in danger or afraid, the caregiver comforts the baby and tries to remove the “threat”. In a not-so-ideal life, the parent becomes angry and aggressive towards the crying baby because mommy didn’t get enough sleep for the last 4 nights in a row.

This safe haven is essential in the first year of a baby’s life. The idea of a “safe haven” is the basis for many theories that support “attachment parenting”. Parents who subscribe to “attachment parenting” try to fulfill the baby’s every need. They breastfeed on demand and sometimes continue breastfeeding well beyond infancy. They prefer to carry their babies as close to them as possible in order to give the baby a sense of comfort and connection. Such parenting theories also suggest babies should sleep with their parents in the same bed for as long as possible, sometimes well into primary school age.

Babies cannot find a safe haven when they are left to cry for a long time, when they are not hugged or remain hungry for too long. Research on babies living in orphanages showed that babies who were not given physical and emotional attention had severe cognitive disabilities.

Healthy babies use crying as a form of communication, but when their basic need for food, physical needs and emotional needs are not met, they learn that communicating does not help them get their needs met and they will stop crying. This can lead to severe attachment problems in adult life.

If this need for a safe haven is not met in the first year of a baby’s life, this can have a severe impact on relationships in adult life. If this component of attachment does not form, this can impair a person’s ability as an adult to seek help and comfort from the people closest to them.

Attachment Theory Part 2: Separation Distress

If you are the person left comforting the baby, with no success, it is important to understand that this discomfort is not a sign that the baby does not like you or that the only person who can care for the baby is mom forevermore. It is simply a sign that the baby sees him/herself as part of mom. The baby has not yet learned that another caregiver can provide a safe haven for them. The baby cannot understand that mom just left for a second to get their water bottle.

Since they still don’t have any concept of time, a second of mom disappearing seems to like forever. Since the baby does not know how to express themselves verbally, crying is their only means of communication.

The caregiver’s reaction when he/she leaves and comes back determines the level of the child’s reaction. We will cover this in more depth in the next chapter.

Attachment Theory Part 3: Secure Proximity Maintenance

According to Attachment Theory, this component of attachment develops when the baby is a bit more mobile. When the baby starts to crawl, they can start to venture out, but they keep constant eye contact with their caregiver to make sure they are close in case of danger. In later years, the child at the playground will make sure the caregiver is always around.

I remember this happening when Noff, my youngest, was one year old. We took an 8 week trip from Melbourne to Brisbane, going through the centre of Australia. We had very full days of hiking and she spent most her time on Gal’s back. By this stage, she had formed attachments with each of the family members, and every time she felt like one of us was missing, she started saying our names as if she was counting to make sure we are all there.

She was already walking at that age so she often wandered around when we took short breaks. If she ever went more than 2-3 meters away, she would stretch out her hand and call for us, as if she was signaling that she wanted us to be closer. She chose 2-3 meters as her security radius. She knew how far she could go and still feel secure.

When parents go beyond their baby’s security radius too often, their babies and toddlers develop a sense of anxiety about being alone. This can lead to future problems such as separation anxiety.

In later years, secure proximity maintenance translates to a desire to be around people who make us feel safe and secure.

Attachment Theory Part 4: Secure Base

They will still wander back to their parents from time to time, just to make sure their caregivers are still around, for comfort or whenever something stressful happens. If the caregiver welcomes the baby back, a secure base will form.

This secure base allows the baby to try new things and still come back without feeling rejected.

A typical example of how a secure base works is a child playing in the playground while the caregiver is sitting with a group of other adults at a nearby bench. When the child falls and hurts their knee, he/she runs back to the caregiver for comfort (a hug, a kiss, an “Oh! That must be painful, let’s wash your hand, everything is fine”).

This secure base will not form if the caregiver is too busy to pay attention when the child comes over (“I am talking now. You have to wait while I finish”) or if the caregiver consider their time with the adults as “time off” and expresses displeasure at being interrupted.

More on Attachment Theory in the next post of the series on the 4 attachment styles: secure, ambivalent, avoidant and disorganized.

Until next time, remember, family matters!

Ronit

This post is part of the series Attachment Theory:

- Attachment Theory: Main Characteristics of Attachment

- Attachment Theory: Four Attachment Styles

- Attachment Theory: Insecure Attachment Style

- Attachment Theory: Secure and Insecure Attachment in Adult Life

- Attachment Theory: Secure and Insecure Attachment in Teenagers

- Attachment Theory: Attachment Styles in Relationships and Marriages