As with the other posts in this series, the points below show that in life, there is no gain without a loss and no loss without a gain. Life is just wonderful that way.

Some of the points were inspired by Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, a highly recommended book Ronit and I have been reading and discussing lately. Other points were just inspired by life.

Armed police

In many of these films and shows, there are many guns and a lot of shooting, and more often than not, the bad guys have a much better arsenal. In the end, the rogue cop with the pistol outsmarts them and saves the day with just a few well-aimed shots and we all have a big satisfied smile on our faces.

Life is a little bit different.

The people who are in biggest danger in Israel are weapon-carrying soldiers. They are the ones getting killed and hurt and it is mostly for their weapons. Some terrorists ignore other defenseless people and target soldiers with guns.

In fact, many of the soldiers who are killed on the roads are shot with their own weapon. Basically, in a war-ridden area like Israel, it is safer not to carry a gun.

In England, police officers carry batons and whistles. Their main weapons while fighting crime are their wits and their authority. The rate of crime involving shooting in England is much lower than in the USA, where there is an arms competition between the criminals and the police. In fact, the rate of “firearms offenses” is dropping dramatically in England and Wales due to this approach.

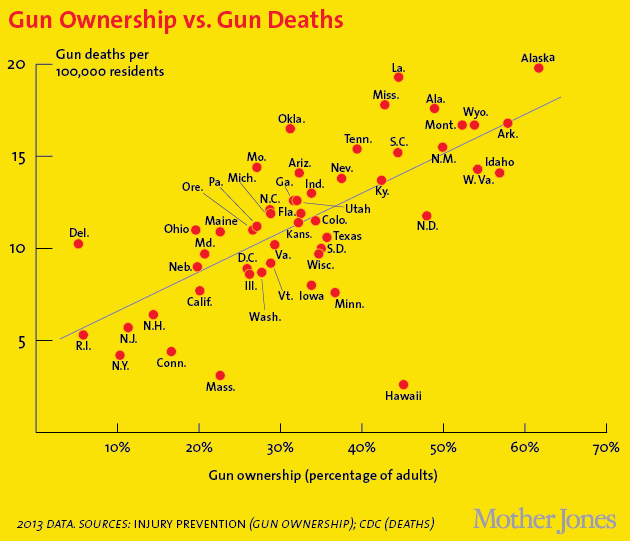

The level of gun ownership world-wide is directly related to murder and suicide rates and specifically to the level of death by gunfire

Professor Martin Killias, International Correlation between gun ownership and rates of homicide and suicide

So theoretically, if we give more guns to the good guys, they will be able to keep themselves alive and protect us better. In reality, the criminals always have more and better guns, because they feel the same way about protecting themselves.

The solution, however counter-intuitive, is to have no guns. Go figure.

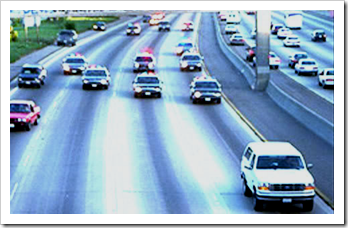

I’m gonna get you!

Say you have something of value and another person damages it. Your first instinct, most likely, is to chase that person and give them a decent flogging.

Unfortunately, when you do that, your brain switches to emotional override mode. You are carried away by your rage, which seems to be valid by virtue of the injustice just caused you, so you stop at nothing. You see only one thing in front of you – the horrible, faceless creature that has caused you harm.

You feel no pain, no fatigue and no sympathy, only righteous anger. You chase and chase and then you catch and hurt (physically or verbally, it does not matter).

It seems that same thing happens to the police. When psychologists interviewed officers after various car chases, they heard the same story over and over again – “I had this adrenaline rush”, “I have no idea how fast I was going”, “I could see the suspect clearly, but I don’t know what else happened (What red light? What pedestrian? What truck?)”

After stopping the hapless offender, police officers made serious judgment errors, ignored proper protocol and even killed or seriously hurt suspects when they were already following their instructions. Some police departments have decided to forbid their officers from giving chase after realizing the extent of damage they were causing.

Again, in this strange world of ours, letting someone get away is sometimes a better choice. With a clear mind, we may reassess the damage and shrug it away or we may find a way to get even. Either way will be better than a chase.

Explaining away our reasons

In a research, supermarket shoppers were given a variety of jams to taste. They had no problem listing their favorites. When compared to a taste-test done with food experts, the results were pretty much the same.

The researchers then asked the experts to explain their choice of jams and got back a list of factors, which they gave to some more shoppers to guide their jam ranking process. The shoppers changed their choices drastically, placing the previous winner near the bottom of the list.

In a dating research, psychologists compared what people specified as their preferred qualities in a partner to the qualities of the ones they felt good about after a brief speed-dating event. Not only was there little correlation between these selections, they were sometimes the exact opposite.

What seems to happen to us is that we make many choices using criteria we are not aware of. When asked to explain our choices or to plan for the best selection, we can only come up with certain things, which often have nothing to do with our ultimate choice.

If you have ever tried to teach something you understand well and gotten stuck, you know how difficult it is. Somehow, many things become clearer when we practice them (playing an instrument, karate, dancing, etc), but there are no words involved and no definitions. Matching those skills with a good description can be surprisingly tough, even when we have mastered the skills.

So next time someone asks you, “Why do you feel this way?” it is OK to answer, “I don’t know. I just do”, because If you try to explain, your reasons may change.

The breach (in the wall) invites the thief

Well, many of us in modern Western society have taken this advice and sealed themselves tightly in – they have built taller and stronger fences, planted trees that block the view, reinforced their doors and installed alarm systems for good measure. They are not sure how many thieves live in their neighborhood. They do it just in case there are any.

In the meantime, friends who come to visit them press a button, wait outside for a while, get looked over through a camera or interrogated through an intercom system, open the door for themselves when they hear a loud and unpleasant buzz and walk themselves in.

Those who are not invited, missionaries and new neighbors alike, are treated with suspicion. Who are you? What do you want?

While on the street, without the protection of solid walls, like has become dangerous. We try to hide our possessions, keep all our valuables where we can feel them and watch everyone carefully. Who knows? They may be thieves…

The social revolution

Our 15-year-old son Tsoof is doing an assignment on public art. He chose to focus on social media, particularly on the effects of digital social interaction on relationships and friendships. We have had some wonderful discussions at home on this subject, which yielded the following topsy-turvy distinctions.

- While our face-to-face friends must live close to where we live in order to sustain our relationship, our digital friends can be anywhere in the world and still be connected to us.

- We can have more digital friends than we can have face-to-face friends.

- Face-to-face interactions take a long time. It is not worth driving 20 minutes to see a friend for 5 minutes and then drive back. Therefore, face-to-face meetings can only happen when we can fit them in. Digital interactions can take seconds and happen any time. In fact, they can happen in one-sided bursts of seconds over a long period (via email, chat, etc).

On the other hand:

- There is a wealth of intuitive information in a personal encounter, which cannot be transmitted online, not even through video. My dad feels I ignore him when we talk on Skype, perhaps because of the high angle of my webcam, which makes me appear like I am looking down at the keyboard, and this gets in the way of intimacy.

- Intimacy is built in relationships over time and in stages. When people live near each other and see each other in natural situations, they learn to trust the same behavior when they see it in the relationship. Online, almost nothing is natural and therefore, it is hard to build deep trust.

- Physical rapport is an intuitive way to make another person feel like we understand them. Professional sales people, psychologists and life coaches learn how to use it deliberately to create the best atmosphere, but we all do it naturally. When all we see is text, physical rapport is impossible. Even when we see the other person’s face and shoulders, but we cannot see them bouncing their knee under the desk, something is seriously missing and we always feel some kind of emotional disconnect or barrier.

- The more relationships we have, the less time we can spend on each of them. This is just simple math. The less time we spend with someone, the less they feel valuable to us and the less we feel valuable to them.

- Being inundated with contacts and updates about our various contacts can be overwhelming to the point where we might consider it a nuisance. But since relationships are meant to be nourishing and energizing, not bothersome, this overload might make isolation seem like a false blessing.

- In many cases, social media activity is more about the number of “friends” listed on our profile than about the relationships we have with them. It is a competition, even with our real friends, which then starts to dominate our offline interactions with them and take over our entire life.

Like I said, it is a weird world out there, full of tradeoffs wherever we go.

Have a wonderful day,

Gal

This post is part of the series Topsy Turvy World:

- Topsy Turvy World (1)

- Topsy Turvy World (2)

- Topsy Turvy World (3)

- Topsy Turvy World (4)