This is the second part of a series of posts about acceptance through the story of Mel, a fascinating client of mine. To know a bit about Mel and how this story started, read Monday’s post, Acceptance (1).

Fairness

Mel thought there was such a thing as Ultimate Justice that all people must follow. She had a very strict concept of Right and Wrong. Fairness was always examined from her point of view and her point of view was the center of the universe. Mel never thought fairness was relative and influenced by culture or upbringing.

Mel thought there was such a thing as Ultimate Justice that all people must follow. She had a very strict concept of Right and Wrong. Fairness was always examined from her point of view and her point of view was the center of the universe. Mel never thought fairness was relative and influenced by culture or upbringing.

When I described to her how the Thai people charged tourists and locals differently at temples or for food, she could not understand how that could be fair. When I gave her an example of a clash between different people’s definition of fairness, she had a “system failure” in her mind.

I remember myself writing protest poems at the age of 14. My notion of fairness was very clear and naïve then. When I was 27, my youngest sister came back from a trip to India and showed me her journal, where she had written, “Is it fair to make your child blind so he can be a better beggar and bring home more money to feed the whole family?” I experience that same “system failure” about fairness at the age of 27, when I tried to answer that question. My immediate reply was, “No, of course it’s not fair!”

But as I thought about it some more, I realized it is not that simple and there is no single right way of doing things. I was already a mother and I was pregnant, which made this realization more difficult, but I understood one big lesson about acceptance: what is fair for one is not necessary fair for another. There is no ultimate fairness. Fairness is totally subjective and we cannot judge others for having a different definition of fairness to ours.

Logic is pure thinking

That is the definition of faith – acceptance of that which we imagine to be true, that which we cannot prove

– Dan Brown

For Mel, everything in life had to make sense. She thought “emotion” was a dirty word and emotional only cluttered the mind. Logic was her weapon against life’s turmoil. She was very puzzled when I told her that I based most of my decisions on gut feelings and that according to the theory of Emotional Intelligence, success in life depends mostly on our ability to recognize and manage our feelings.

For Mel, everything in life had to make sense. She thought “emotion” was a dirty word and emotional only cluttered the mind. Logic was her weapon against life’s turmoil. She was very puzzled when I told her that I based most of my decisions on gut feelings and that according to the theory of Emotional Intelligence, success in life depends mostly on our ability to recognize and manage our feelings.

When Mel talked about feelings, she talked about them from a scientific point of view. When I asked her, “What do you feel towards your husband and your kids?” she said, “I love them”, but whereas my definition of love was a vague feeling of warmth and happiness, she had a clear scientific definition, saying, “I know it is love when I want to be with them, when I want to do things for them, when I think that…”

For Mel, everything had conditions. Whenever I needed to explain a feeling, I would find an example and say, “It’s like when you…” Mel always sounded as if her descriptions had come out of a dictionary.

I do not think I know what pure thinking is, but there is nothing pure in precise definitions and putting conditions on every action. Logic is no cure for heartache and pain, because there are many things around us without logic and Mel refused to accept them.

When I asked her to imagine a great future that made sense to her, she said, “There is no logic in bringing images into the mind, because imagining them does not make them reality”. I told her how Gal had come up with an image of the kids coming home after school and everyone having a great afternoon together, and how it had happened exactly the way he had imagined it on the same day. She stood there confused and nodded as if telling me, “I know you are telling me the truth, Ronit, but it still makes no sense”. Until the end of our coaching, dreaming of a happy future was not a technique that worked for Mel.

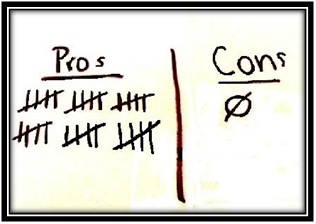

Advantages and disadvantages

Mel thought that making every decision could only happen after a thorough analytical thinking process of weighing advantages and disadvantages. At first, I thought it was a good idea.

Mel thought that making every decision could only happen after a thorough analytical thinking process of weighing advantages and disadvantages. At first, I thought it was a good idea.

I once saw a movie about a relationship coach who took all his female clients on a date and sat in a restaurant facilitated their process of weighing the pros and cons of leaving their husbands on a napkin. He helped all of them go back to their husbands. In our family, we call this method “The Napkin Technique”.

But it was not as simple with Mel, because she did not settle for just listing advantages and disadvantages. She also had to weigh each of them differently. This was still manageable, because I used KT Analysis for assigning a weight to each item and adding them all up, but then Mel added short term, medium term and long term considerations and that really messed up the napkin.

“What about doing things because you want to or feel like doing them?” I asked her.

She seriously did not know what that meant.

“You know, just like kids do, without too much thought. Where do these things come from?” I kept asking.

I thought that being so self-conscious about everything meant not accepting the fact that we are human – we cannot plan everything we do and cannot weigh every choice and decision. To herself and to everyone else, Mel looked like a procrastinator, because instead of living life, she was contemplating every little movement as if she was searching for an exact number that meant it was going to make her happy. Mel could argue about everything for so long there was no point when she could decide what to do about it.

Making decisions was not her strongest ability and she felt she was not controlling her life, because things kept happening to her while she was trying to make her mind up.

Frustrated fortuneteller

Mel really believed that logic, a strong sense of fairness and her ability to analyze things could make her come up with the “right” decision. She repeatedly said, “He should have done that”, “It should have worked”, “It was supposed to be…” Accidents and mistakes were not part of her vocabulary. Every future was supposed to be perfect, exactly the way she expected it to be. That way, she sentenced herself to life in the prison of frustration.

Mel really believed that logic, a strong sense of fairness and her ability to analyze things could make her come up with the “right” decision. She repeatedly said, “He should have done that”, “It should have worked”, “It was supposed to be…” Accidents and mistakes were not part of her vocabulary. Every future was supposed to be perfect, exactly the way she expected it to be. That way, she sentenced herself to life in the prison of frustration.

To all my clients, I say that when you play Solitaire, you need to look a few steps ahead in order to predict the future outcome of your actions. I can go in my mind 5-6 steps ahead, but I cannot cover all the possibilities. Life it is a very big Solitaire game and there no chance in Hell we can predict every step of the way.

To help me survive my inability to “play God” and predict the future, I often read the Serenity Prayer:

God, grant me the courage to change the things I can, the serenity to accept the things I cannot change and the wisdom to know the difference

Mel had never experienced serenity, because she thought there was nothing in the world she could not change.

I told her that on a wonderful day, a day that was supposed to be one of the happiest days of my life with the birth of my son, turned out to be one of the saddest days of my life, because he died from a heart defect. Mel looked at me with teary eyes. I could see in her eyes the endless loop of examining the options. I remembered myself in that loop. I had never thought there was nothing I could not change, because I had figured out by then I could not change my height, my parents or the past.

I think that story hit her hard. “Couldn’t they find he had a heart defect in an ultrasound?” she asked desperately.

“I had done 4 ultrasounds and they hadn’t”, I told her.

“Maybe it’s the person who had done the ultrasounds?” she pleaded.

“I’d had a total of 6 ultrasounds done by 6 different people in 2 different countries”, I replied.

“Maybe if you had done one closer to the delivery, the heart would have been big enough to notice the defect”, she kept going.

“2 of the ultrasounds were done the week before he was born”, I said.

“Isn’t there a special ultrasound that can find such things?” she could not let go.

“There is, but you can only get it if you’ve had a baby with a heart defect already, but my daughter was perfectly healthy and my pregnancies were great”, I explained.

“Well, that’s good, right? Because it meant that with the next child, you could do that special ultrasound”, she said.

“I could and I did. I had a baby girl with a perfect heart, but she had a cord accident and died inside me on the 32nd week”, I told her.

“No!” Mel said in anguish, but I knew she had finally gotten it, the hard way.

We cannot control everything that happens to us, but we can control how to respond. Trying to predict everything that will happen and being frustrated it does not happen the way we have predicted it is like being a bad fortuneteller that cannot come to terms with their inability to tell the future.

Allergic to mediocrity

Mel could not settle for less than the best. She wanted to be the best mom, the best wife, the best daughter and teacher and expected the same from others. She talked a lot about her students being lazy, stupid and slow. She was very surprised when I told her I was kicked out of school in 10th Grade because I had no idea what the teachers were talking about in Physics, Biology and Chemistry.

Mel could not settle for less than the best. She wanted to be the best mom, the best wife, the best daughter and teacher and expected the same from others. She talked a lot about her students being lazy, stupid and slow. She was very surprised when I told her I was kicked out of school in 10th Grade because I had no idea what the teachers were talking about in Physics, Biology and Chemistry.

“Why would you tell me you’re not good at something?” she asked, surprised. For her, being good at everything was the ultimate desire and she was convinced it was the same for everyone.

“Because I’m not”, I said, “Are you good at everything?”

She thought about it for a while and said, “Well, eventually I will be! If I’m not good at it now, I will become good”.

“Great, so eventually you’ll be a great mother, wife and lecturer”, I said.

She looked at me and smiled with understanding. Nobody is good at everything all the time. Not even Mel. And that is OK.

Mel had no understanding of different abilities. When I taught her about communication styles and how we each learn differently, she was shocked. “Do you mean that when I explain something to my students, not everyone understands the same?” she asked and looked like she was in pain when I said it was true.

Mel was one of those rare digital people who could learn things in a flash and memorize many details. From time to time, when I explained things, she would say to me, “Ronit, you’ve said that already”. I explain things from different angles to make sure things are clear, but she only had to hear everything once and could not imagine other people might need more than one example.

It was a challenge for Mel to be surrounded by so many “stupid” people who need so much time and so many examples to understand something. So we spent a long time questioning Mel’s definition of stupidity. The best way I could do this was by giving myself as an example. For Mel, giving myself as an example was a brave act of admitting my “stupidity”. Accepting we were “wired” differently gave Mel a key to understanding herself and others. Later on, she changed her teaching methods and even the way she interacted with her kids. She then started to say that “maybe they aren’t that stupid”.

Accept everything about yourself. I mean everything. You are you and that is the beginning and end – no apologies, no regrets

– Clark Moustakas

Motives and reasons

For Mel, everything had a reason and every person had a motive, but she could not figure the reason or the motive. When we talked about the unfairness of the world, people had reasons to be mean to her and motives to fight with her. She was always on guard. For the whole year that we met on my balcony and in our emails, Mel kept torturing herself by assuming people have bad motives and wanted to harm her.

I told her that in her mind, the world was not safe and she needed to trust that people are good and the things they do are not against her. People do everything because they believe that, in some way, they will benefit from doing it.

One day, when we discussed motives, I told Mel about our experience of giving free hugs at the Queen Street Mall in Brisbane. We went out 4 times and each time, many people stood there and asked suspiciously, “Why do you do this?”

Mel immediately said, “I would’ve asked exactly the same question. Why on Earth would you go and hug total strangers on the street?”

“We wanted to make people feel good”, I said.

“How do you feel good by giving people hugs?” she asked.

It was very funny. That happened on the street too. Some people said to me, “OK, I’ll give you a hug” and others said, “Sure, I’ll have a hug”. People like Mel thought they were giving me a hug and doing me a favor, whereas I thought hugs were a two-way street – you give and receive at the same time.

“It’s a wonderful feeling to hug and be hugged by hundreds of people”, I told Mel.

“Even if you don’t know them?” she asked, really curios to know my motives, “Didn’t you take some advertising flyers?”

“No”.

“Why not?”

“Why not?”

“Because we wanted to advertise hugging, not Be Happy in LIFE“, I said.

“What did you tell people?” she asked.

“That they needed 12 hugs a day to keep the doctor away”, I told her.

When we talked about motives, she wanted to know why I did the things I did and my answer, “To feel good”, just did not sink in. When I talked to her about drawing, she could not understand why I would bother to draw or paint if I was not a professional artist, my art would not be displayed anywhere and I would not be paid for it. Doing things for fun was not a valid motive for Mel.

Some of the sessions seemed like she was conducting a research on me. She asked me questions and I answered them. She wanted to know how I thought and why I did the things I did. I sometimes said I did not really know why I had chosen to do something. I sometimes do things just because I have a feeling they will be the right things to do. Mel said feelings could not be measured, so they were not a good tool to measure motives and reasons.

Acceptance is not submission. It is acknowledgment of the facts of a situation, then deciding what you are going to do about it

– Kathleen Casey Theisen

More acceptance on Friday…

See you then,

Ronit

This post is part of the series Acceptance:

- Acceptance (1)

- Acceptance (2)

- Acceptance (3)